Roads Less Traveled: Innovative Options in Transportation for People with Disabilities

by Adrianne Murchison

David Bryan, like many folks, rises early in the morning, gets dressed and goes to work. Getting there, however, with ease and peace of mind is a relatively new luxury for David, who has an intellectual disability. On work days, a driver with Lyft comes by to take him to his place of employment at The Epstein School, located five miles away from home, and brings him back later in the afternoon.

“I like it a lot,” said David. “It saves a lot of time.”

He has taken these pre-scheduled Lyft rides through a Medicaid waiver since January. It’s part of a Medicaid pilot program inspired and initiated by Carol Pryor, a local mother, who was in search of an avenue that would pay for her daughter Jenny’s travel to work.

“I have been an advocate for my daughter here in Georgia for over 25 years, so I know the infrastructure,” said Pryor. “Looking at the infrastructure on anything is how you roll it out, and that’s what I love to do.”

David and Jenny receive Lyft services through Medicaid in two different ways, yet the mode of transportation has been impactful for them both.

David, 46, had previously relied on MARTA Mobility for travel to work. “Lyft has made a big difference for him in a short period of time; it’s giving him an opportunity to have a really nice lifestyle,” said Allan Bryan, David’s father.

Since utilizing Lyft, David can sleep an extra hour on work mornings, and he’s back home within 15 to 45 minutes after the end of his work shift. Whereas the MARTA van would at times arrive at the school up to an hour and a half after David got off work, Bryan said.

A Mother on a Mission

For years, there has been a need for increased transportation services for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Some people, such as Carol Pryor, have addressed the need with a passion. She returned to the Atlanta area in 2017 after living in Florida, North Carolina and south Georgia for several years while still being her daughter’s advocate for services.

“There comes a point where it’s safer to take an alternative form of transportation,” Carol said, regarding the limited options.

Jenny, 38, paid Lyft car service to drive her to work at a nearby Kroger bakery for a year and half. At that point, her mother stepped in to see how funds in Jenny’s Prior Authorization (PA) budget with Medicaid could cover the cost.

Pryor, with the help of others, found the answer within four months. “Every Medicaid waiver recipient has a PA budget, and there is a line item for transportation,” she said. “It shows the different services that are provided to that individual. Transportation is among the services that is offered through Medicaid waivers.”

Pryor discovered that Jenny’s transportation funds had not been used in six years. A task at hand was to connect Jenny’s need for Lyft transportation to the corresponding line item in her PA budget.

“She was taking Lyft to work every day and paying out of her own money, which is a limited amount,” said Pryor. “The maximum amount allocated to funding for transportation in her PA budget is $2,797 per year. There was no way to take that transportation funding for a vendor such as Lyft ride-sharing services, and have it paid through the Medicaid waiver.”

Pryor credits her vast work experience with state and federal government, as well as the corporate world, in providing her with the ingenuity to bring Lyft and Medicaid together.

As an advocate for Jenny, she had been in ongoing communication with someone in participant-directed services at the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD) for about a year before returning to Atlanta.

“They had been looking for an answer as well,” said Pryor. “I met with them and told them that I came to Atlanta to try to be helpful in their search for an answer.”

The key was to see if Lyft met criteria under DBHDD guidelines for common or commercial carriers, as well as criteria under regulations for participant-directed services, which would allow Medicaid to pay for the transportation.

The answer was yes to both.

Before contacting Lyft to make her request for a transportation program to benefit adults with disabilities, Pryor then brainstormed a name for the program in the making: Georgia Medicaid Waiver Lyft Transportation Initiative.

“I found the executives in top leadership at Lyft and I said that I was a part of creating a [transportation initiative for adults with disabilities] in Georgia and we would like to talk to Lyft about being a part of it,” recalled Pryor.

The ask was simple: the ride-share service would provide individuals with disabilities transportation to work in supported employment.

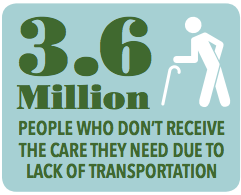

Lyft was on board with the idea. A company statement for this article noted data by the American Hospital Association that says a lack of transportation prevents 3.6 million people per year from getting the care they need.

Source: American Hospital Association“Connecting underserved communities with transportation is central to Lyft’s mission to improving people’s lives,” the statement said. “And we envision a world where access to transportation is frictionless, affordable and reliable.”

Source: American Hospital Association“Connecting underserved communities with transportation is central to Lyft’s mission to improving people’s lives,” the statement said. “And we envision a world where access to transportation is frictionless, affordable and reliable.”

Pryor views a Lyft/Medicaid partnership as something greater than a major accomplishment.

“Corporations and state agencies and federal agencies speak two different languages,” she explained. “This is one of the miracles of this project. This is a part of Lyft’s inclusion. They want to be a part of community inclusion for all.”

Jenny would become the first client in the Georgia Medicaid Waiver Lyft Transportation Initiative.

But beforehand Lyft, along with Pryor and Jenny’s fiscal agent, PCG Public Partnerships (who oversees her budget and pays expenses) created a Medicaid auditable process that includes a request form for incremental amounts from Jenny’s PA transportation funds.

“Every time Jenny takes a ride the amount is deducted,” said Pryor. “Every month, I submit a Lyft ride history report to the participant-directed manager at DBHDD.”

From Jenny’s perspective, Lyft is a smooth ride. She simply calls them when she needs transportation to work or elsewhere.

“Before Lyft, I was asking people to take me to work,” Jenny said. “It was a bit of a challenge. Now I feel more independent. I can take myself places and leave when I want. I’ve met drivers from around the world: Iran, Iraq, Vietnam, Korea, China and Colombia. I even rode in a Tesla. It was great.”

Another Road to Transportation

While Jenny receives Lyft services through Medicaid’s participant-directed services, David’s transportation funds are allocated under provider services. Pryor accomplished this for him with Jean Millkey of Jewish Family and Career Services (JFCS), which is a concierge partner with Lyft.

David, whose wife also has a developmental disability, has been a part of the JFCS independent living program for nearly 30 years.

“I have private clients that come to me, and I advocate for them for Social Security benefits, or whatever is needed,” said Pryor. “During an ISP (Individualized Service Plan) meeting, I realized David did not have a dedicated line item for transportation in his PA budget.”

Pryor worked with the support coordinator responsible for overseeing David’s care, services and Medicaid waivers to add an addendum for transportation and a line item for funding.

Through STAR (Service Change/Technical Assistance Requests), the support coordinator responsible for David’s services facilitated the addition of transportation funding in his PA budget.

JFCS provides Alterman/JETS Transportation to adults with developmental disabilities and senior citizens offering rides to work and other destinations on weekdays.

“We have a fleet in house and a small staff of paid drivers,” said Millkey, JFCS office and transportation manager.

“It is a big help, but when you consider the time constraints [of JETS], we wanted to expand,” said Millkey. “Lyft was a logical way to expand when we don’t have drivers.

“David goes through JFCS as a concierge partner with Lyft. We have access to their ride scheduling system and can schedule unlimited rides up to one week in advance.”

The Lyft concierge portal offers additional benefits for David, as well as other Lyft riders, who are not in the pilot transportation program.

“We can monitor where the Lyft driver is by looking at a screen and call them, if necessary, and say, ‘Not that building, this one,’” said Millkey. “So, it gives some security to seniors and those with developmental disabilities, who are intimidated by the thought of arranging their own ride.

“Lyft then bills us by the month and we in turn get payment from the client or the program. So that means David does not have to set up his own account with a credit card.”

For now, David and Jenny are the only two participants representing the pilot models for the Georgia Medicaid Waiver Lyft Transportation Initiative, and it appears unlikely that there will be others in the near future.

“It’s on our radar and is something we want to pursue,” said Amy Riedesel, DBHDD Director of Community Services.

“This is a pilot project of the [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services]. The department stands behind it and recognizes the [value to recipients]. There are waiver amendments that are being considered and this is not one of them at the moment.”

If you support the waiver amendment to expand the Lyft pilot program, you can email Amy Riedesel at or call her at 404-657-7858 to let DBHDD know.

Georgia Town Creates Transit System

Reliable transportation can be more than life-changing; it can be life-saving. About 185 miles outside of Atlanta in Fitzgerald, GA, Jill Alexander helped to bring a transportation van service to citizens with disabilities, senior citizens and others in need.

Before the existence of Ben Hill Transit, many people who use wheelchairs would find their way to appointments or shopping destinations by navigating along sidewalks and streets.

“Two people were killed,” said Alexander. “One person would take the back alleyways and she would get herself flipped over.”

Alexander now resides in Gainesville, GA, however, Fitzgerald was her home for 35 years. Before moving away in 2012, she generated a groundswell of support for transportation for people with disabilities.

“I was a community builder for the Georgia Council on Developmental Disabilities (GCDD),” she said. “My [son] has developmental disabilities. I had a navigator team through Parent to Parent. I had taken Partners in Policymaking training and sat on the Council as an advisor. I started to gain interest in the issue by talking about the problem and got the ball rolling.

“[GCDD] started to support me, and they got people to rally around the [idea of a] transportation system.”

The first city official that Alexander approached directly laughed at the idea of the town creating a transit system, but she was not deterred. She held community talks with the elderly; visited apartment residents; and sought to understand how easy or difficult it was for people with mental health problems to visit the mental health center in Tifton for medication and appointments.

“We put together a survey – a kind of needs assessment,” said Alexander. “I started connecting groups and spurring interest and organized a town hall meeting. We had a phenomenal turnout.”

By that time, Alexander had decided to turn to people running for public office, such as Philip Jay, who would become a Ben Hill County Commissioner and is former executive director of The Jessamine Place, which advocates for people with disabilities and provides support services.

Source: Kaiser Health News, 2016“I saw a very legitimate need for it,” said Jay. “We had folks who were walking everywhere. Walmart is a couple of miles out of town for most folks, and the streets aren’t safe for pedestrians or wheelchairs.”

Source: Kaiser Health News, 2016“I saw a very legitimate need for it,” said Jay. “We had folks who were walking everywhere. Walmart is a couple of miles out of town for most folks, and the streets aren’t safe for pedestrians or wheelchairs.”

People First of Georgia, an advocacy group for people with disabilities became interested, and GCDD’s Real Communities had an active role in helping Fitzgerald figure out a path to bringing a new transit system to town.

“Real Communities brings people with and without disabilities together to address local problems,” said Eric Jacobson, GCDD executive director. A team met with citizens and local political leaders to determine what assets already existed there that could assist in the need for a transit system.

“Our job was to publicize,” Jacobson said. “This was a community-based effort. The community decided on a local special option sales tax as a way of building their own transit system.

“We funded Jill to be a community organizer during that time period, and get local folks talking about transportation.”

Ben Hill Transit System Vans started in Fitzgerald on July 1, 2015 with three vans. There are now six vehicles.

The Federal Transit Administration pays up to 45% of the cost for the transit system, according to Michael Erwin of Resource Management Systems, which operates the service. “The rest is made up by the purchase of service contracts that we as operators of the system procure … to provide trips at a minimal cost to riders.”

Van rides are scheduled 24 hours in advance. A regular one-way ride is $3. There can be half-priced rates for senior citizens, veterans and others in need, he added.

Last November, members of Fitzgerald, including Alexander and Shirley Brooks, current executive director of The Jessamine Place, made a presentation at the University of Georgia’s Institute on Human Development and Disability, on how they created Ben Hill Transit.

“The transit system is for everyone in the community,” said Brooks. “It’s kind of amazing to me when I see the vans go by.”

Alexander expected to always live in Fitzgerald and see her now 22-year-old son become active in the community. “I saw a lack of transportation as a huge barrier for him to interact in the community,” she said in recognizing, “the need be a participant in the community and not just a bystander.”

Allan Bryan has similar sentiment when it comes to David.

“David has been working since he graduated from high school,” said Bryan. “He even worked at a hotel in Toco Hills, and they kept cutting back bus service [in that area] which made it difficult to get around. Lyft is giving him a great opportunity to get around and enjoy what everyone else does.”

Watch Fitzgerald’s story of how they created a transportation system for people with disabilities.To read more in Making a Difference magazine, see below:

Download the pdf version of the Spring 2019 issue.

Download the large print version of the Spring 2019 issue.